- This topic has 2 replies, 3 voices, and was last updated 5 years, 2 months ago by .

Vocational Training the e-Learning Way

Home › Forums › Woodworkers United! › Hello Class!

Tagged: hello, introduction

I’m really looking forward to this class.

Nice to meet you Steve. I look forward to working with you in this class.

Nice to meet you Steve. I’m looking forward to seeing you progress through this program.

Use this chat box to contact support for any technical issues with your Learning Management System. Please DO NOT use this for questions relating to your course learning material.

Brown-rot fungi break down hemicellulose and cellulose that form the wood structure. Cellulose is broken down by hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) that is produced during the breakdown of hemicellulose. Because hydrogen peroxide is a small molecule, it can diffuse rapidly through the wood, leading to a decay that is not confined to the direct surroundings of the fungal hyphae. As a result of this type of decay, the wood shrinks, shows a brown discoloration, and cracks into roughly cubical pieces, a phenomenon termed cubical fracture. The fungi of certain types remove cellulose compounds from wood and hence the wood becomes a brown color.

Brown rot in a dry, crumbly condition is sometimes incorrectly referred to as dry rot in general. The term brown rot replaced the general use of the term dry rot, as wood must be damp to decay, although it may become dry later. Dry rot is a generic name for certain species of brown-rot fungi.

Soft-rot fungi secrete cellulase from their hyphae, an enzyme that breaks down cellulose in the wood. This leads to the formation of microscopic cavities inside the wood, and sometimes to a discoloration and cracking pattern similar to brown rot. Soft-rot fungi need fixed nitrogen in order to synthesize enzymes, which they obtain either from the wood or from the environment. Examples of soft-rot-causing fungi are Chaetomium, Ceratocystis, and Kretzschmaria deusta.

Kretzschmaria deusta, commonly known as brittle cinder, is a fungus and plant pathogen found in temperate regions of the Northern Hemisphere. It is common on a wide range of broadleaved trees including beech (Fagus), oak (Quercus), lime (Tilia), Horse Chestnut and maple (Acer). It also causes serious damage in the base of rubber, tea, coffee and palms. It causes a soft rot, initially and preferentially degrading cellulose and ultimately breaking down both cellulose and lignin, and colonises the lower stem and/or roots of living trees through injuries or by root contact with infected trees. It can result in sudden breakage in otherwise apparently healthy trees. The fungus continues to decay wood after the host tree has died, making K. deusta a facultative parasite. The resulting brittle fracture can exhibit a ceramic-like fracture surface. Black zone lines can often be seen in cross-sections of wood infected with K. deusta.

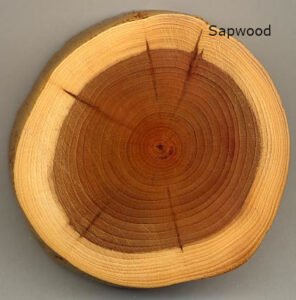

The actively conducting portion of the stem in which tree cells are still alive and metabolically active is referred to as sapwood.

In the living tree, sapwood is responsible not only for conduction of sap but also for storage and synthesis of biochemicals. An important storage function is the long-term storage of photosynthate. Carbon that must be expended to form a new flush of leaves or needles must be stored somewhere in the tree, and parenchyma cells of the sapwood are often where this material is stored. The primary storage forms of photosynthate are starch and lipids. Starch grains are stored in the parenchyma cells and can be easily seen with a microscope.

Heartwood functions in long-term storage of biochemicals of many varieties depending on the species. These chemicals are known collectively as extractives. In the past, heartwood was thought to be a disposal site for harmful byproducts of cellular metabolism, the so-called secondary metabolites. This led to the concept of the heartwood as a dumping ground for chemicals that, to a greater or lesser degree, would harm living cells if not sequestered in a safe place. We now know that extractives are a normal part of the plant’s system of protecting its wood.

Extractives are responsible for imparting several larger-scale characteristics to wood. For example, extractives provide natural durability to timbers that have a resistance to decay fungi. In the case of a wood like teak (Tectona grandis), known for its stability and water resistance, these properties are conferred in large part by the waxes and oils formed and deposited in the heartwood. Many woods valued for their colors, such as mahogany (Swietenia mahagoni), African blackwood (Diospyros melanoxylon), and Brazilian rosewood (Dalbergia nigra),owe their value to the type and quantity of extractives in the heartwood.

For these species, the sapwood has little or no value, because the desirable properties are imparted by heartwood extractives.

White-rot fungi break down the lignin in wood, leaving the lighter-colored cellulose behind; some of them break down both lignin and cellulose. As a result, the wood changes texture, becoming moist, soft, spongy, or stringy; its color becomes white or yellow. Because white-rot fungi are able to produce enzymes, such as laccase, needed to break down lignin and other complex organic molecules, they have been investigated for use in mycoremediation applications.

There are many different enzymes that are involved in the decay of wood by white-rot fungi, some of which directly oxidize lignin. White-rot fungi are grown all over the world as a source of food – for example the shiitake mushroom, which in 2003 comprised approximately 25% of total mushroom production.